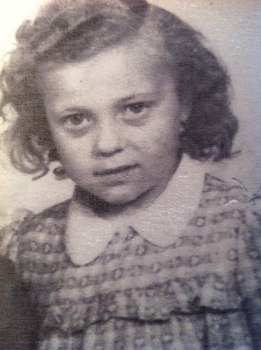

Natalia Orloff-Klauer

I will always remember the war years of my childhood. Though we survived the Holocaust, my parents and siblings have not escaped the pain.

In 1941, the Nazi invaded Ukraine, my Motherland, and their objective was to annihilate the Ukrainians not to liberate them. Like Joseph Stalin in 1932-33 tried to kill the Ukrainians by starvation. My 2 older sisters and my aunt (who was 12 years old) barely survived that horror. We lived in Tomakovka at that time. As the Germans invaded untold thousands of civilians were rounded up, shot and buried in mass graves.

After setting up their operational head quarters, the Germans learned our family was one of two in Tomakovka who spoke German and my mother was put to work as a translator for a period of time. Mother knew that refusing would mean a death sentence for our entire family. My older sister, Nelly, (14 years old) had to shine their boots and wash their clothes while they lived in our home.

Because Germany had so many men in uniform, there was a tremendous shortage of workers at home to support the war industry. The German solution to this problem was to use slave laborers on a massive scale to relieve the shortage.

German army kidnapped young adults off the streets and shipped them to Germany as slave laborers to work in the most dangerous conditions. Forced labor camps were established throughout Germany. Thousands died in these camps from disease, starvation, allied bombings and harsh working conditions. The demand for more and more workers to replace the dead increased. My cousins and uncles were rounded up and transported to Germany. My sister, Nelly, was spared this fate because she could speak German and was put to work by the Nazis as a telephone operator for the military communications.

In February 1943 after the crushing defeat at Stalingrad the inevitable German retreat began. The Germans rounded up entire towns and villages along the way and transported men, women, and children to Germany to re-supply the slave labor camps. My family was included in this round up.

After our 350 mile journey to the Polish border on foot, we were loaded onto a railcar crowded together like cattle. Approximately every 8 hours the train would stop near a river or stream for about 30 minutes. Everyone jumped out and ran to the water to quench their thirst, wash up or rinse out dirty diapers.

Allied fighter planes once strafed our train. The train stopped, everyone ran for cover, diving into ditches, behind rocks and anywhere else that might offer cover. When the planed disappeared the engineer gave a short blast of the whistle to indicate the train was about to leave.

After several days our train arrived in Saarbrucken in October 1943 a city southwest of Germany near the French border. It was a large train depot and a major transportation center in the area. From Saarbrucken, we were transported to Bibigan (a slave labor camp) a few miles from the city. The camp had several hundred men, women, and children. We lived in a barracks with 15 other families and slept on metal bunk beds. The only privacy was provided by a blanket that separated our family from the rest.

The workday began when the wake-up siren sounded in the camp at 4 a.m. For breakfast a cup of black coffee and 3 oz. of bread. The coffee was made from toasted acorns grounded up. The bread was mixed with sawdust to give it texture and help fill our empty stomachs. Lunch was delivered to various work sites. It consisted of a few vegetables floating in warm water. Supper we would wait in line with our tin cups to be filled with a ladleful of turnip soup and a half a loaf of bread for the six of us. Sometimes there was not enough food for everyone in the camp and we went to sleep hungry. My 2 year old brother lost so much weight he looked like a skeleton covered in loose skin.

At 6 a.m. roll call and work assignments were handed out. Older women were required to watch and care for the infants and young children while the mothers were sent out on various work details. All were forced to wear black overall with ID patches. OST for the East Slavic countries, P for Poland, F for French, etc. There were different color patches for political prisoners, Jehovah’s Witness, a criminal, a homosexual, etc. This made it easy for camp guards to identify the workers. In the fall of 1944 my mother became ill with TB. She never recovered and died several years after the war ended at the age of 42.

In December 1944, Allied forces were advancing to the German border. Air raid sirens would sound day and night. In the middle of December we were ordered to pack up our belongings. We were being relocated to another camp in Germany. No one knew the destination.

On Christmas Eve 1944, our train arrived in Dresden, Germany. We were housed in a large brick building near the center of the city. When we first saw Dresden, we could not believe our eyes. Dresden appeared untouched. Thousands of refugees fleeing from the advancing Soviet army filled the city. We began hearing rumors of the impending surrender of Germany. The rumors gave everyone hope that after all we might survive this terrible ordeal.

Early February 1945 we were told on February 16 our family along with others would be transferred to Chemnitz (a sub camp of Flossenburg concentration camp) near the Czechoslovakian border. The transfer to Chemnitz never took place as Dresden was about to be destroyed by the British and American bombers. Shortly after 10 p.m. on February 13, 1945 the saturation of fire bombing of Dresden by the British began. Hundreds upon hundreds of British bombers dropped thousands of tons of incendiary bombs setting much of Dresden center on fire. A second bombing raid was timed several hours later. The next day over 300 American B-17 bombers dropped nearly 800 tons of bombs on the city. When the people heard the sirens the first night, they felt they would be safe since Dresden had remained untouched all the years of fighting. No one could have anticipated the horror that was about to be unleashed that night. Here is one survivor’s account of what happened.

“It is not possible to describe! Explosion after explosion. It was beyond belief, worse than the blackest nightmare. So many people were horribly burnt and injured. It became more and more difficult to breathe. It was dark and all of us tried to leave this cellar with inconceivable panic. Dead and dying people were trampled upon; luggage was left or snatched up out of our hands by rescuers. The basket with our twins covered with wet cloths was snatched up out of my mother’s hands and we were pushed upstairs by the people behind us. We saw the burning street, the falling ruins and the terrible firestorm. My mother covered us with wet blankets and coats she found in a water tub. We saw terrible things: cremated adults shrunk to the size of small children, pieces of arms and legs, dead people, whole families burnt to death, burning people ran to and fro, burnt coaches filled with civilian refugees, dead rescuers and soldiers, many were calling and looking for their children and families, and fire everywhere fire, and all the time the hot wind of the firestorm threw people back into the burning houses they were trying to escape from. I cannot forget these terrible details. I can never forget them.”

Lothar Metzer (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1945_Dresden_bombing)

To this day, my sister Anna remembers the sickening smell of burnt human flesh and the anguish of survivors searching for their loved ones. Dresden was in chaos. There was no order anywhere in the city. No electricity, water, or food. Rescuers were digging through the rubble for survivors. Others worked to clear the streets so that tankards of water pulled by horses could be delivered to the desperate civilians. People packed any vehicle still able to move and overloaded every train leaving Dresden in an effort to escape. Most, however, were forced to walk. Then without warning, Allied fighter planes would suddenly appear and fire their cannons at anything moving on the ground. Only by the grace of God were we able to survive the horror of those 2 days.

After the war, we made our way to Morfelden, Germany. Before we could leave the camp we had to be deloused. Everyone had lice. Many heads were shaved. Everyone was stripped bare and we had to line up naked in front of strangers. That was very humiliating to my two teenage sisters. We were referred to as Displaced Persons. We lived in a damaged railcar for a few months till father found a small 2 room cottage in rundown condition built to house Germans made homeless by the war. We were happy with this place.

In 1948, Congress passed and President Truman signed the Displaced Persons Act of 1948. In 1949, my father applied for a visa under the provisions of The Act.

We arrived in America in June 1950. We were sponsored by the Grace Presbyterian Church of Wichita, Kansas. Ed and Betty Williams members of the church became our personal family sponsors. They would become our second family.

Over 47 million civilians were lost in this terrible war. We must always be vigilant and speak out against such evils of intolerance and bigotry that may result and lead inevitably to war. War is hell and there are no winners.

Freedom is precious and we must always preserve it.